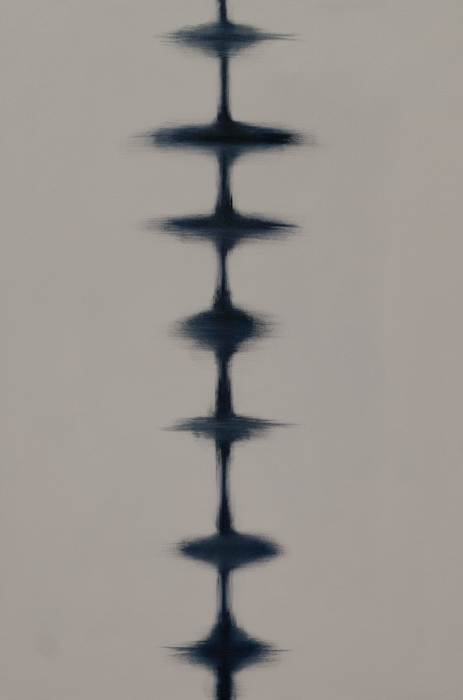

River Fleet water, glass bottle, cork, sealing wax, wire, Thames driftwood, jute.

Left on Talacre Road, London NW5.

Museums, Art History, Art

River Fleet water, glass bottle, cork, sealing wax, wire, Thames driftwood, jute.

Left on Talacre Road, London NW5.

River Fleet water, glass bottle, cork, sealing wax, wire, Thames driftwood, jute.

Left on Fleet Road, London NW3

River Fleet water, glass bottle, cork, sealing wax, wire, Thames driftwood, jute.