Londonist has an article about London’s Lost Museums, including the Theatre Museum, the Cuming Museum, and the Bramah Tea and Coffee Museum. You could argue that not everything featured in the article is a museum – the London Planetarium, for example – but it’s a nice sampling of the diversity of now-lost venues.

Category: Lost Museums

Cardiff Bay then and now

Part of my PhD on museum closure is about the Welsh Industrial and Maritime Museum. The museum stood on the waterfront of Tiger Bay, the part of Cardiff once filled with canals and large docks. In the late 1980s and 1990s, the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation redeveloped the area, renaming it as Cardiff Bay in the process. During the redevelopment, the Corporation bought the industrial museum’s site and sold part of it to a property developer. The Mermaid Quay shopping centre opened on the site in 1999.

These photos show the transformation of the bay area. The bay was tidal, and mud flats were exposed when the tide was out. That changed when the bay was enclosed with a barrage to raise the water level to a consistent height. The black and white photos were taken in 1979, two years after the Welsh Industrial and Maritime Museum opened. I took the colour photos in February 2022.

Types of museum closure

I’ve written a blog for the Mapping Museums project on types of museum closure. It’s the first published product of my ongoing PhD research. As I write in the blog:

Not all museums close in the same way. My own research into museum closure in the UK over the last sixty years shows that there are different types of museum closure, and some have more impact: they are more final than others.

Read the whole piece here: http://blogs.bbk.ac.uk/mapping-museums/2020/04/29/types-of-museum-closure/

The Barnes Museum of Cinematography

John Barnes was a noted film historian, who opened the Barnes Museum of Cinematography in St Ives in Cornwall in 1963, together with his wife Carmen. It was one of the first film museums, and the first in Britain. Thousands visited each year, and it attracted scholars from across the world.

The museum displayed a collection that John had acquired with his twin brother William over many years. The Barnes brothers tried to persuade public bodies in England to set up a permanent museum to house the collection, but were unsuccessful. A plan to move the museum’s collection to London also came to nothing, and the museum closed in 1986. The collections were dispersed, many of them to other museums. Objects from the era before cinema, including magic lantern slides, went to the Museo Nazionale del Cinema in Turin. The parts of the early cinema collection that related especially to England went to Hove Museum and Art Gallery where they are still on display.

This film is a tour of the museum, from the entrance door covered in photographs by Eadweard Muybridge to the most modern exhibit – a 1918 cinema projector. In between, Barnes demonstrates early moving image devices such as a thaumatrope and a praxinoscope, ‘What the butler saw’ machines, and early cinema cameras.

John Barnes was born in 1920 and died in 2008. He and his brother had started making films when still teenagers. You can watch one of them, about farming in Kent in the 1930s, on the British Film Institute Player.

The Royal Architectural Museum

The story of the Royal Architectural Museum, which was dogged by financial difficulties and had to move premises twice in the span of fifty years before closing at the start of the 20th century.

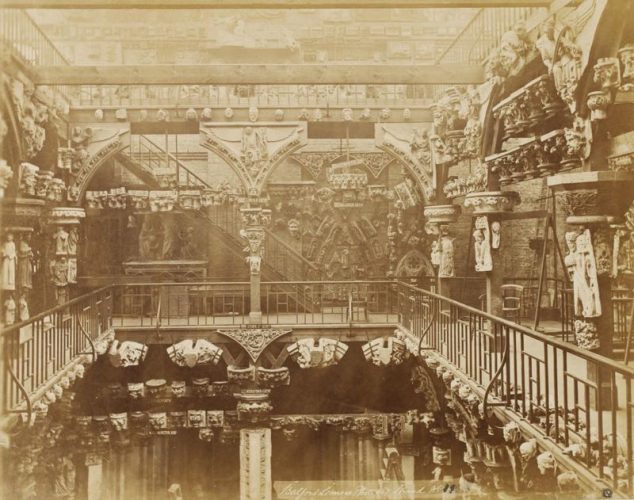

Since 1844 British architects had been calling for a collection of national antiquities. In 1851 George Gilbert Scott wrote to The Builder with a plan for a Government funded ‘Public Museum of Mediaeval Art’ and emphasised the necessity of such a museum for the Gothic revival, then the dominant architectural style. (One of Scott’s best-known buildings is the Midland Grand Hotel, the frontage of St Pancras Station. Another example of the style is Pugin and Barry’s Houses of Parliament.) Scott had been prompted to write partly because of the impending sale of the architect Lewis Cottingham’s Museum of Mediaeval Art. At the time there were three main collections of architectural casts in London: John Soane’s museum, another at RIBA, and the Government’s Design School Museum at Somerset House, founded in 1837. The latter museum was in disarray by the late 1840s.

The aim of a new collection was to reinvigorate the practice of Gothic stone carving by making sure that art workers had access to good quality examples. In 1852 rooms were taken above horse stables at a wharf along Cannon Row in Westminster and the museum opened that August. The museum included a school, run by Charles Bruce Allen, but it had only eleven students in 1853. The school closed temporarily in 1854 due to freezing conditions, before being closed down completely due to a lack of funds. In the meantime more rooms had been taken to house the growing collection. By 1855 the collection included more than 6,500 objects including 3,500 casts and 1,500 brass rubbings.

The museum faced financial problems including rent increases and the withdrawal of a Board of Trade grant, but it was offered rent-free space at the new South Kensington Museum (which later became the Victoria & Albert Museum). In 1857 the Architectural Museum was moved to first-floor galleries at Kensington. Still under financial pressure, the museum attempted to renew its Government grant. This was met with a counter-offer that the museum lend its collection to the South Kensington Museum and relinquish control. Although the museum’s committee initially rejected this proposal, they eventually relented and loaned the collection to the host museum in 1860-1. But it soon became clear that the collection was being neglected, and disagreements between the South Kensington Museum and the Architectural Museum led to a search for new premises.

It was offered a site in Bowling Street (Tufton Street from 1870), a return to Westminster not far from where it had begun. Donations of money, materials, and labour made the new building affordable, and the project was given a fillip by Queen Victoria’s agreement to extend royal patronage. The museum became the Royal Architectural Museum, and opened in its new premises in July 1869.

Continuing its original educational purpose, a school for architectural drawing was opened in 1870. As before the intended beneficiaries were art workers and lectures were arranged to encourage their attendance. Money continued to be a problem for the museum but the school did well, taking over the whole of the top floor in the 1880s. With about two hundred students the school was effectively subsidising the museum and changed its name to Westminster School of Art in 1890.

The building and collections were taken over by the Architectural Association in 1902, giving them new premises for a tiny fraction of the estimated cost of a new building elsewhere. But the collections were neglected. Architectural tastes had changed and the Association wanted more space, so the casts were transferred to the South Kensington Museum or dispersed elsewhere. Having occupied three different locations and weathered continuous financial pressures, the museum had closed for good.

In 1916 the building was taken over by the National Library for the Blind, then demolished in 1935 for new headquarters. Much of the museum’s collections remain in the V&A, identified on their labels as gifts of the Architectural Association.

Images copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, except the exterior drawing of the Museum from The Builder (vol 27, no.1381, 24 July 1869, p.587). [view at archive.org]

This article is indebted to research by Edward Bottoms (https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhm006)

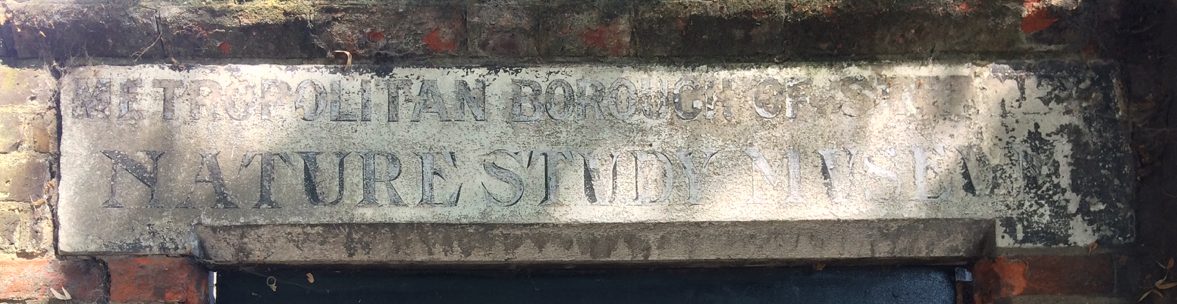

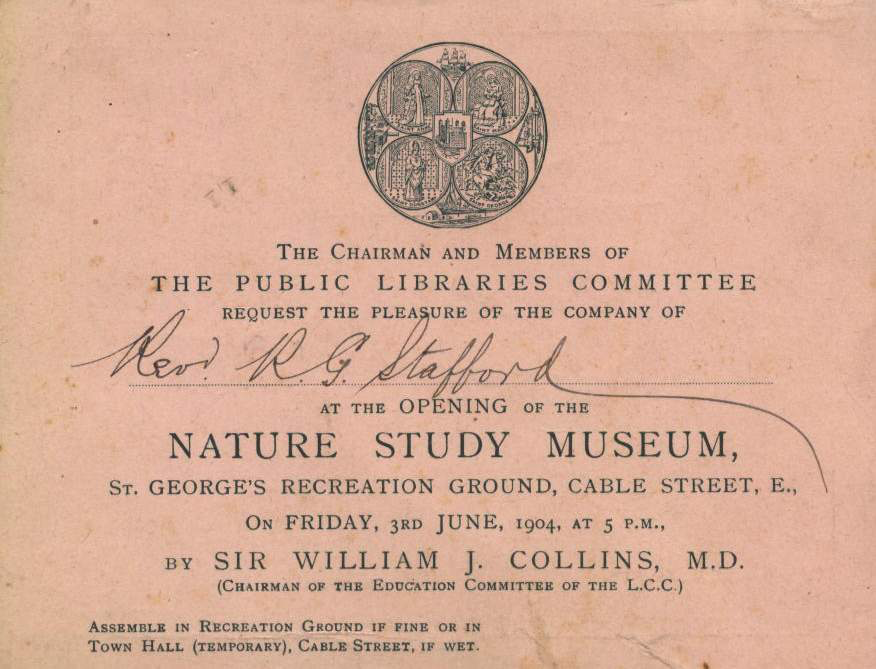

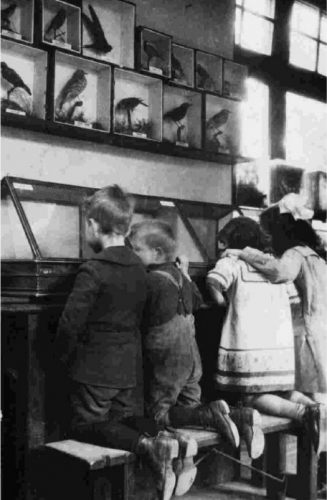

St George’s Nature Study Museum

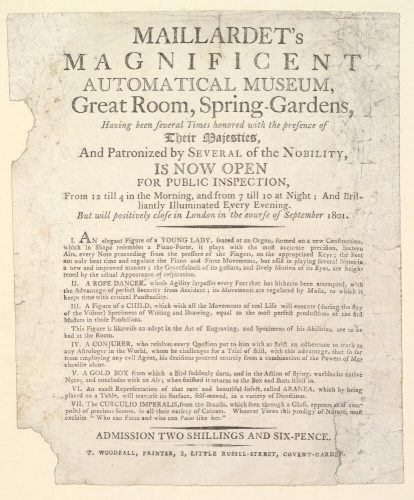

Maillardet’s Automatical Museum

In 1798, Henri Maillardet decided to move his Automatical Exhibition to new premises. Business must have been good, because the Great Room in Spring Gardens was advertised as offering ‘better accommodation’ than the house in Howland Street, not far from Fitzroy Square. The new venue was also close to Charing Cross, a much more central location than Fitzrovia. Maillardet ran his ‘Magnificent Automatical Museum’ in Spring Gardens from 1798 to 1817. The Museum’s exhibits included automata of a lady playing sixteen different Airs on an organ, a child who both wrote and drew, a Conjurer, and a rope dancer. Maillardet also showed miniature automata in the forms of an Ethiopian caterpillar, an Egyptian lizard, and a Siberian mouse. He was the London representative of Jaquet-Droz, a family of Swiss clockwork specialists who also made automata.

Maillardet also exhibited elsewhere at the same time. In 1812 ‘Philipstal and Maillardet’s Automatical Theatre’ was open in Catherine Street, Covent Garden. In the 1820s, some time after the Museum closed, the collection was on show at the Gothic Hall in Haymarket, and it was advertised for sale in 1828. The child writer automaton ended up in Philadelphia. It was destroyed in a fire, but parts of the mechanism survived and were fashioned into a new figure by experts at the Franklin Institute.

This video is the best of a selection featuring the automaton on Youtube.

And here’s a very brief view of one of the Ethiopian Caterpillars.

The handbill is in the collection of the Bodleian Library, shared under a Creative Commons Licence.

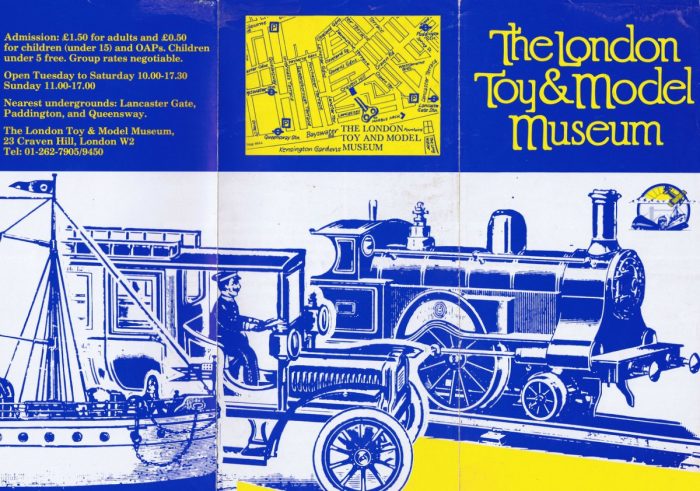

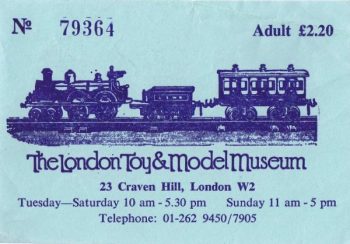

The London Toy and Model Museum

The London Toy and Model Museum was open for seventeen years in two town houses in Craven Hill, not far from Paddington Station. Appropriately enough, one of its exhibits was a Paddington Bear that once belonged to the young Jeremy Clarkson. As the brochure and ticket suggest, the emphasis was on transport and the collections included model railways of various sizes, including a ride-on miniature railway around a pond.

Also on show was a model Victorian fairground with organ music, and a working coal mine fourteen feet long and eight feet high, made by a Welsh miner named William Phelps. The model mine had been displayed at the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 and took Phelps twenty years to make.

Founded by two toy collectors in 1982, the museum was later bought by the Fujita Corporation which spent £5.5 million pounds on refurbishing it. Fujita was run by Kazuaki Fujita, also a toy collector. The museum had 120,000 visitors a year and employed thirty people. In 1999, four years after Fujita’s death, the Corporation decided to close the museum saying it was no longer affordable. The collections were auctioned by Sotheby’s.

There are still museums partly or wholly devoted to toys in London. Pollocks was established in the 1950s and occupies a lovely old building in Scala Street. Amongst the displays is a large collection of toy theatres. And the Museum of Childhood, a museum with a fascinating history of its own, has been in East London since 1872 when it opened as the Bethnal Green Museum. Initially a rather diverse collection of objects with no clear theme, it began to become more oriented towards children from the 1920s, and was eventually reopened as the Museum of Childhood in 1974.

Images via Brighton Toy and Model Museum

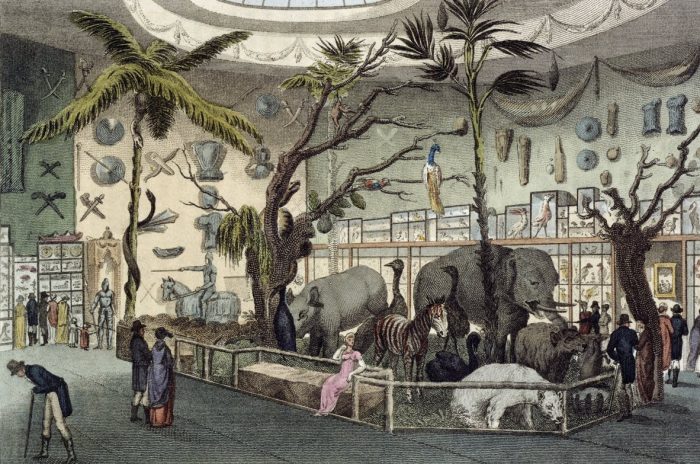

William Bullock’s Egyptian Hall

A nineteenth century cabinet of ‘natural curiosities’

William Bullock (1773–1849) opened a Museum of Natural Curiosities in Liverpool. He brought the collection to London, showing it first in the Liverpool Museum at 22 Piccadilly.

Bullock then commissioned the construction of the Egyptian Hall, officially known as the ‘London Museum and Pantherion’, which opened on Piccadilly in 1812. By then the collection included ‘upwards of Fifteen Thousand Natural and Foreign Curiosities, Antiquities, and Productions of the Fine Arts’. Bullock was a member of the Linnaen Society, which was devoted to the study of biology, and presented his exhibition ‘for the advancement of the Science of Natural History’. The ‘Pantherion’ was a kind of diorama that presented wild animals and plants as if in their natural habitats, ‘a beautiful illustration of the luxuriance of a torrid clime’. This included a giraffe, a rhino, wild cats, monkeys, porcupines, and many others.

As well as animals and plants, Bullock’s collection included crafts, clothes, weapons, and works of art. Ever the showman, he organised a display of Napoleonic relics in 1815–16 and made £35,000 from the venture. Among the exhibits was Napoleon’s bullet-proof carriage, later sold to a coach maker and eventually bought by Madame Tussauds. The Hall’s contents were sold at auction in 1819 and it continued as a temporary exhibition venue throughout the nineteenth century. It was demolished in 1905.

Bullock produced illustrated catalogues to accompany his exhibitions, some of which are available online. Archive.org has a copy of the 12th edition, published in 1812.

North Woolwich Old Station Museum

North Woolwich station was once home to a small railway museum, but is now derelict. The station opened in 1847 as one terminus of the Eastern Counties and Thames Junction railway. It provided access to some of the docks as well as a connection with the Woolwich Ferry. The nearby Royal Victoria Dock opened in 1855, although the railway cut across the dock entrance and a swing bridge had to be built to carry it. The line was taken over by the North London Railway in the same year the station opened, and it remained as a working terminus for the North London Line until December 2006.

The station building was used as a ticket office until 1979, when a new entrance building opened further along the remaining working platform. Five years later a museum opened in the old station building, dedicated to the history of the Great Eastern Railway. The GER was formed in 1862 and took over the running of the North London Line.

The museum contained all kinds of railway memorabilia including a locomotive and signalling equipment. Although it was run by the London Borough of Newham, the Great Eastern Railway Society contributed to the displays. The museum closed in 2008, apparently due to financial difficulties. The collections were dispersed to various institutions, but the building remains under the management of a charity, a successor to the Passmore Edwards Trust. Unfortunately the owners have been unable to find a buyer for the building and today the station is clearly derelict. The doors and windows are boarded up, scrawny buddleias cling to the balcony, and paint is flaking off the rear canopy. But the fading signs of its former uses still remain on the station’s façade.

Museum photos copyright 2004 Owen Dunn.

Building photos in 2018 by the author.