“The daily papers talk of everything except the daily. The papers annoy me, they teach me nothing”. Georges Perec wrote these words in 1973, but they seem just as relevant today. The froth of news, with its focus on dramatic events and a scorning of the ordinary, could not have been further removed from Perec’s own preoccupations. He focussed on the stuff of everyday life – the comings and goings of people in the street, the way a flock of pigeons flies around a city square, the objects on his work table. Things that many might overlook – what Perec sometimes referred to as the ‘infra-ordinary’ – were for him the main interest.

In that respect, his concerns overlap with those of the Japanese artist On Kawara. Kawara focussed on time, location, movement and the simple fact of being alive. He made paintings of dates, sent postcards which record the time he got up that day, and recorded his movements around the place where he lived. Both men in their different ways focussed on the everyday, the facts of life which many take for granted.

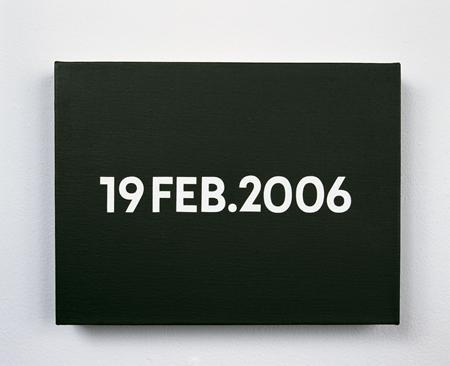

On Kawara is probably best known for his date paintings. Each was made during a single day and showed the date on which it was made, in the format customary to the place where Kawara made it. If he was in a place which did not use a Roman script, he substituted Esperanto. The date was always painted in white, centred on the canvas and in a sans-serif font similar to Futura. The background colour varied. Jan 4, 1966 is an Ultramarine Blue. May 31, 1970 is grey, while Mar.10,1978 is bright red. The background was not simply applied as one colour. According to Christian Scheidemann, Kawara applied under-layers of reddish brown, burnt umber and natural umber with a hint of blue until the colour reached a “deep, profound, indefinable darkness”. The lettering was created carefully, again applied in a number of coats of white with special attention being paid to the edges. The finished paintings appear precise and close to machine-made.

This rather impersonal aspect was apparent in other works by Kawara.

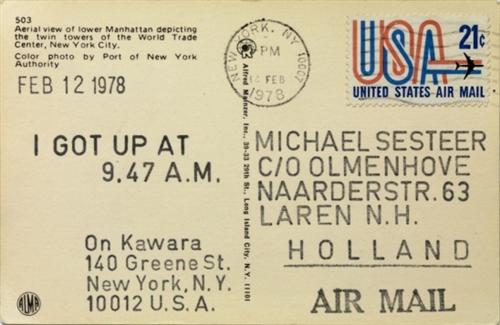

A series of telegrams sent since 1970 stated baldly “I am still alive”. How would you respond if you received a message like this? It’s possible to perceive it as a rebuke, at the very least a reminder. It states perhaps the most basic fact – I still exist. A series of postcards gave slightly more information about the artist’s life: the time at which he got out of bed on a specific day. But this information is again rendered impersonally. All the text on each card is rubber-stamped: the sender’s and recipients’ addresses, the date, and the message are all printed in a similar font. Each card is of the kind a tourist would be likely to send – a view of the place where Kawara happened to be at the time.

Kawara catalogued many things: what he read during each day – ‘I Read’, the people he met – ‘I Met’, and where he went – ‘I Went’. This showed his movements that day traced in red biro on a black and white photocopied map. The map for May 18 1974 shows his movements around downtown Manhattan, while on 18 Fev 1973 he traced his steps around a small block of streets in Casablanca. Nowadays with the prevalence of GPS and smartphones, tracing your daily movements has become commonplace, but in the 1970s this would have been something of a novelty.

This cataloguing of everyday activities in a matter-of-fact manner is one aspect in which On Kawara’s work overlapped with that of Georges Perec. Perec catalogued everything he ate in a single year – or almost everything – in Attempt at an Inventory of the Liquid and Solid Foodstuffs ingurgitated by me in the course of the year Nineteen Hundred and Seventy Four. In Kawara’s hands, such lists would likely have had a page for each day with a list of food and drink. Instead, Perec accumulates: “One apple pie, four tarts, one hot tart, ten tarts Tatin, seven pear tarts, one pear tart Tatin, one lemon tart, one apple and nut tart, two apple tarts, one apple tart meringue, one strawberry tart”. The list continues in a similar vein for over five pages.

On a similar theme, in 1976 Perec published Notes Concerning the Objects that are on my work-table. Less of a list than a musing on the various objects that clutter his desk, he dwells on where he keeps things and why, the history and functionality of his ashtrays, and the process of clearing, cleaning and rearranging his work table.

A few years before, Perec had set out something that resembled a manifesto for this attitude to observing life: Approaches to What?. He decried the undue attention received by spectacular events such as disasters, and indeed anything deemed worthy of front page headlines, suggesting that it was only in those cases that certain things which we take for granted started to have any existence for us. “Aeroplanes achieve existence only when they are hijacked”, he wrote. “The one and only destiny of motor-cars is to drive into plane trees”.

Instead of focussing on spectacular incidents, Perec would have us pay attention to everything to which we have become habituated, the everyday, those things we use without thinking, the places we inhabit, the ordinary, even what he called the infra-ordinary. He visited the Rue Vilin, a nondescript street in northeast Paris where he lived until he was five, on at least six occasions between 1969 and 1975. His first visit is an extensive catalogue of what he can see including the variety of shops, the wordings on their signs, the slope of the street and more. On subsequent visits he documents the changes as shops close, buildings are boarded up or knocked down, and new buildings constructed. What emerges is a picture of a street in flux – a picture of change as much as of the buildings and other details he sets down.

He took a more intensely detailed approach in another text: An Attempt at Exhausting a place in Paris. Over a period of three days in October 1974, Perec sat in cafes and on park benches in place St Sulpice and noted what he witnessed going on around him. In keeping with his aim of recording the infra-ordinary, he wanted to describe “what happens when nothing happens other than the weather, people, cars and clouds”. He records the buses and their destinations, the movements of the pigeons, the comings and goings of shoppers and church-goers, the manoeuvres of people parking their cars, occasional meetings with people he knows, his orders of food and drink and much more besides.

This is as far from the sensational as we could probably get. There are no headline-grabbing events, just a close inspection of life as it is lived by the vast majority of people. Both Perec and Kawara went about this in the simplest way possible: recording and cataloguing. Most dates are not remembered unless something significant happened, but Kawara dignified dates seemingly at random simply by making a painting that day. His and Perec’s lists of everyday activities elevate the ordinary, that which we would not normally pay much attention to, into something out of the ordinary. Their work stands as an antidote to the newspaper headline and the attention-grabbing link on a blog. Here is where life is really is, they seem to be saying. All you have to do is look.