The story of the Royal Architectural Museum, which was dogged by financial difficulties and had to move premises twice in the span of fifty years before closing at the start of the 20th century.

Since 1844 British architects had been calling for a collection of national antiquities. In 1851 George Gilbert Scott wrote to The Builder with a plan for a Government funded ‘Public Museum of Mediaeval Art’ and emphasised the necessity of such a museum for the Gothic revival, then the dominant architectural style. (One of Scott’s best-known buildings is the Midland Grand Hotel, the frontage of St Pancras Station. Another example of the style is Pugin and Barry’s Houses of Parliament.) Scott had been prompted to write partly because of the impending sale of the architect Lewis Cottingham’s Museum of Mediaeval Art. At the time there were three main collections of architectural casts in London: John Soane’s museum, another at RIBA, and the Government’s Design School Museum at Somerset House, founded in 1837. The latter museum was in disarray by the late 1840s.

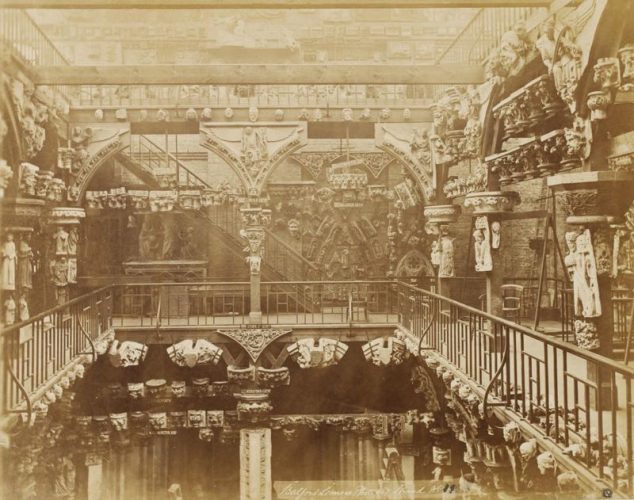

The aim of a new collection was to reinvigorate the practice of Gothic stone carving by making sure that art workers had access to good quality examples. In 1852 rooms were taken above horse stables at a wharf along Cannon Row in Westminster and the museum opened that August. The museum included a school, run by Charles Bruce Allen, but it had only eleven students in 1853. The school closed temporarily in 1854 due to freezing conditions, before being closed down completely due to a lack of funds. In the meantime more rooms had been taken to house the growing collection. By 1855 the collection included more than 6,500 objects including 3,500 casts and 1,500 brass rubbings.

The museum faced financial problems including rent increases and the withdrawal of a Board of Trade grant, but it was offered rent-free space at the new South Kensington Museum (which later became the Victoria & Albert Museum). In 1857 the Architectural Museum was moved to first-floor galleries at Kensington. Still under financial pressure, the museum attempted to renew its Government grant. This was met with a counter-offer that the museum lend its collection to the South Kensington Museum and relinquish control. Although the museum’s committee initially rejected this proposal, they eventually relented and loaned the collection to the host museum in 1860-1. But it soon became clear that the collection was being neglected, and disagreements between the South Kensington Museum and the Architectural Museum led to a search for new premises.

It was offered a site in Bowling Street (Tufton Street from 1870), a return to Westminster not far from where it had begun. Donations of money, materials, and labour made the new building affordable, and the project was given a fillip by Queen Victoria’s agreement to extend royal patronage. The museum became the Royal Architectural Museum, and opened in its new premises in July 1869.

Continuing its original educational purpose, a school for architectural drawing was opened in 1870. As before the intended beneficiaries were art workers and lectures were arranged to encourage their attendance. Money continued to be a problem for the museum but the school did well, taking over the whole of the top floor in the 1880s. With about two hundred students the school was effectively subsidising the museum and changed its name to Westminster School of Art in 1890.

The building and collections were taken over by the Architectural Association in 1902, giving them new premises for a tiny fraction of the estimated cost of a new building elsewhere. But the collections were neglected. Architectural tastes had changed and the Association wanted more space, so the casts were transferred to the South Kensington Museum or dispersed elsewhere. Having occupied three different locations and weathered continuous financial pressures, the museum had closed for good.

In 1916 the building was taken over by the National Library for the Blind, then demolished in 1935 for new headquarters. Much of the museum’s collections remain in the V&A, identified on their labels as gifts of the Architectural Association.

Images copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, except the exterior drawing of the Museum from The Builder (vol 27, no.1381, 24 July 1869, p.587). [view at archive.org]

This article is indebted to research by Edward Bottoms (https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhm006)