William Bullock (1773–1849) opened a Museum of Natural Curiosities in Liverpool. He brought the collection to London, showing it first in the Liverpool Museum at 22 Piccadilly.

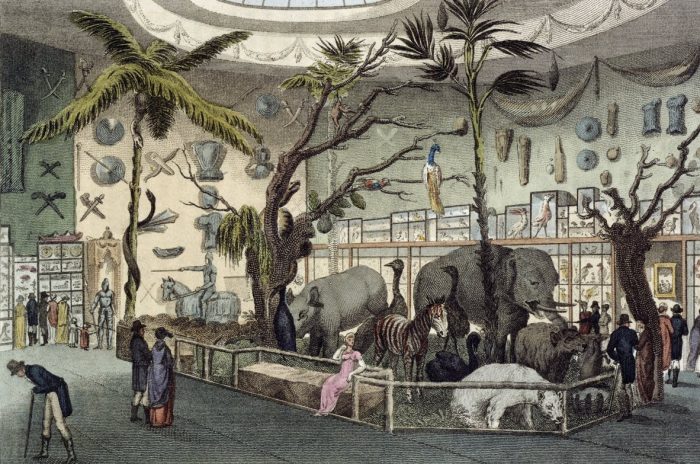

Bullock then commissioned the construction of the Egyptian Hall, officially known as the ‘London Museum and Pantherion’, which opened on Piccadilly in 1812. By then the collection included ‘upwards of Fifteen Thousand Natural and Foreign Curiosities, Antiquities, and Productions of the Fine Arts’. Bullock was a member of the Linnaen Society, which was devoted to the study of biology, and presented his exhibition ‘for the advancement of the Science of Natural History’. The ‘Pantherion’ was a kind of diorama that presented wild animals and plants as if in their natural habitats, ‘a beautiful illustration of the luxuriance of a torrid clime’. This included a giraffe, a rhino, wild cats, monkeys, porcupines, and many others.

As well as animals and plants, Bullock’s collection included crafts, clothes, weapons, and works of art. Ever the showman, he organised a display of Napoleonic relics in 1815–16 and made £35,000 from the venture. Among the exhibits was Napoleon’s bullet-proof carriage, later sold to a coach maker and eventually bought by Madame Tussauds. The Hall’s contents were sold at auction in 1819 and it continued as a temporary exhibition venue throughout the nineteenth century. It was demolished in 1905.

Bullock produced illustrated catalogues to accompany his exhibitions, some of which are available online. Archive.org has a copy of the 12th edition, published in 1812.